Full post coming soon.

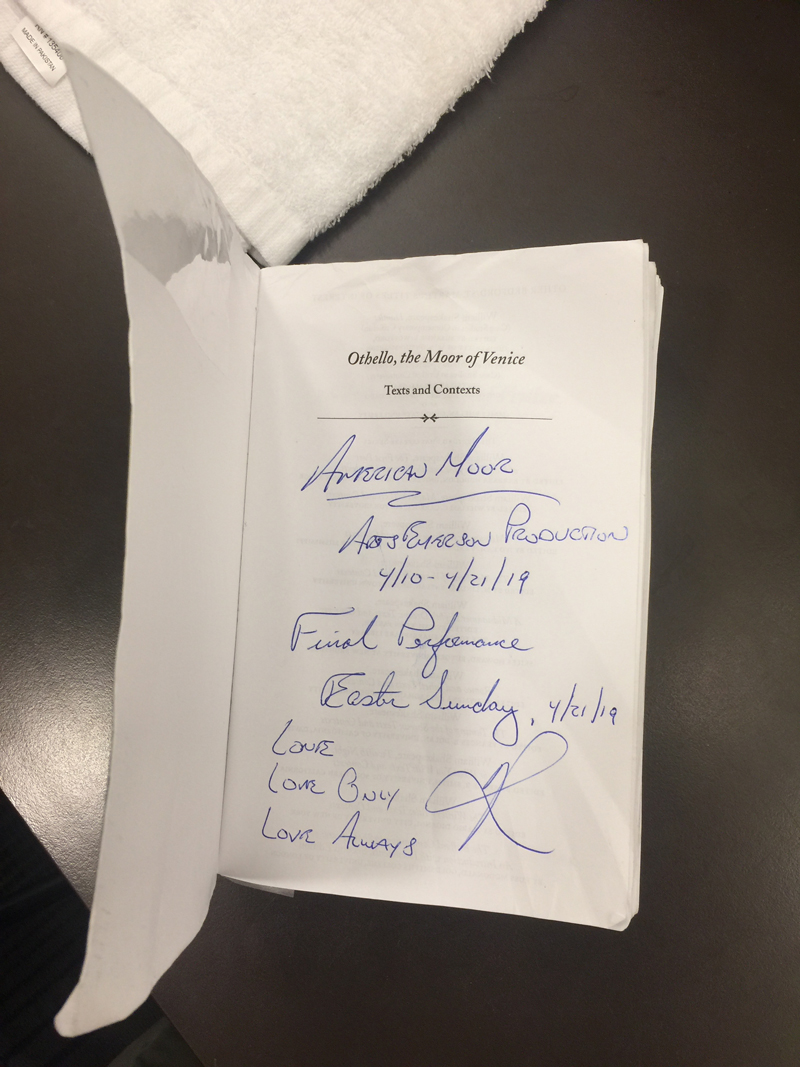

Turning The Page

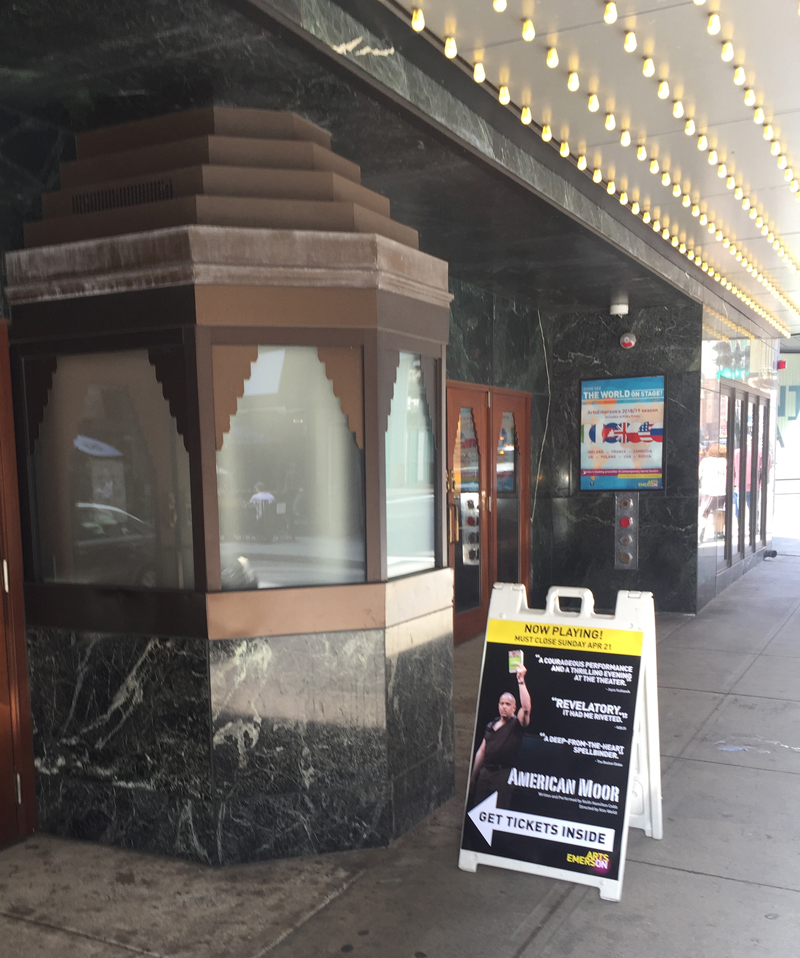

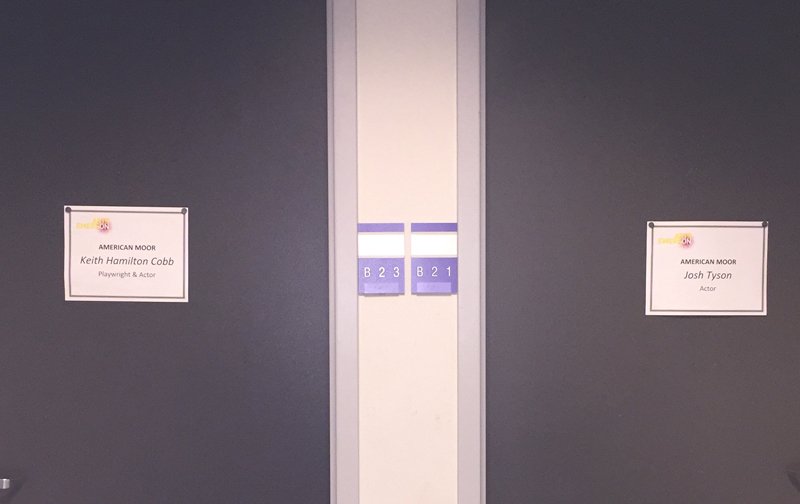

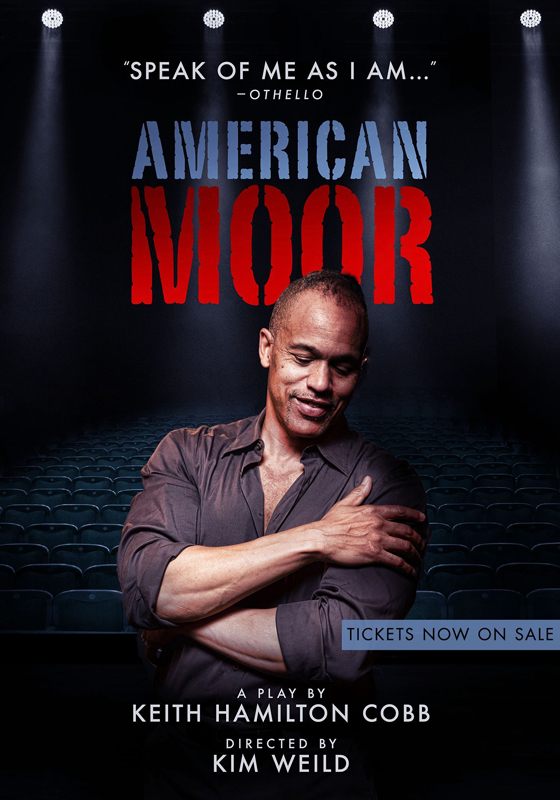

American Moor at ArtsEmerson in Boston Ushers in the Newest Chapter in The Performance Life of an American Play

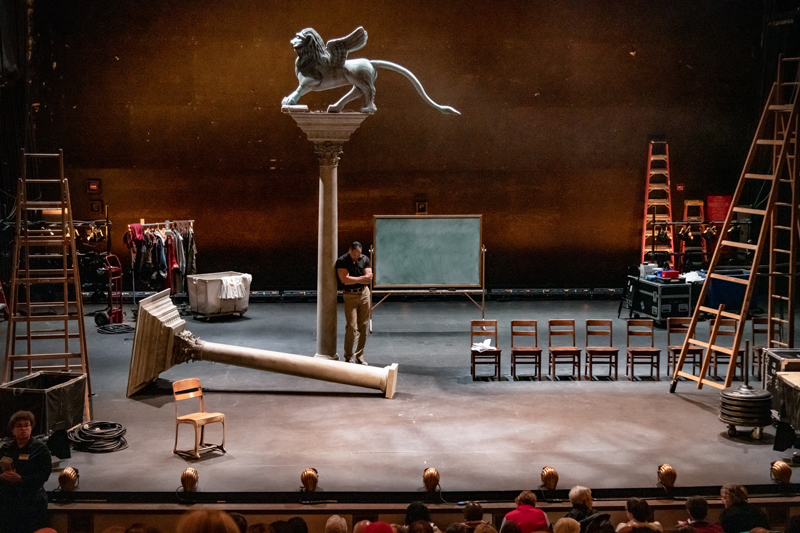

The first public performance of American Moor was at Westchester Community College on November 20, 2013. The first drafts of the play were set to paper approximately a year prior to that. So the ArtsEmerson production of American Moor on the Robert J. Orchard Stage at the Paramount Center for the Arts in Boston, MA marked six and a half years of development and performance. It was the culmination of the good faith and intention of a small group of theatre makers and top-shelf designers who brought to the stage in April the play as we had never seen it, never experienced it… It was perhaps the play that we were never completely sure we were looking for until we all found it together. The thrill of those revelations we shared with audiences experiencing the play for the first time. They had never seen anything like it either…

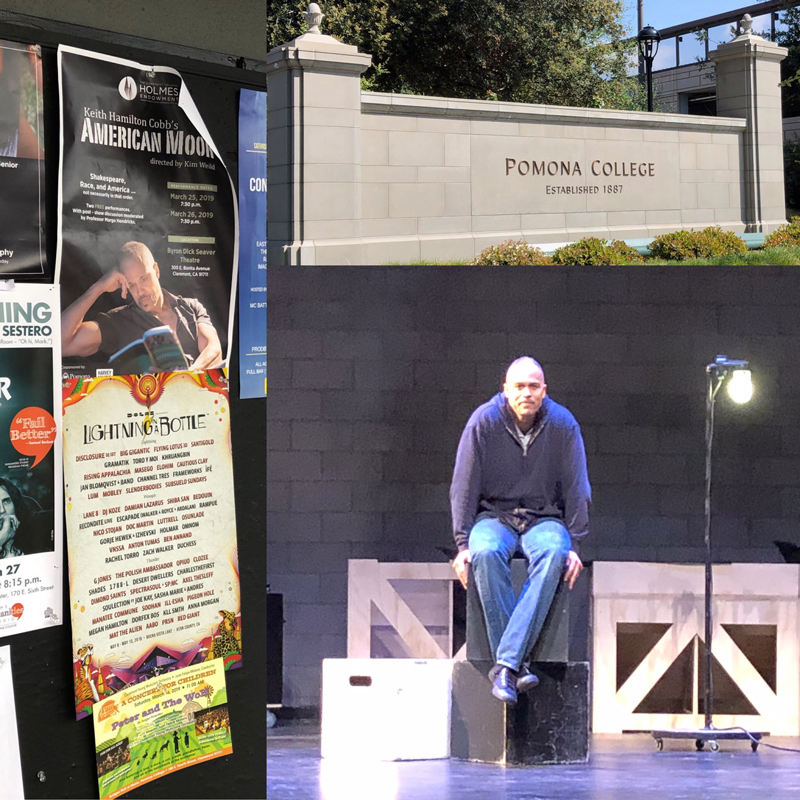

January, 2019 through the closing date in Boston on Easter Sunday had been a whirlwind of travel, multiple stages, diverse audiences, and a last dash towards something definitive. The photos below are a montage of the DC, LA, London, and Boston.

Washington, DC

Los Angeles, CA

London, England

Boston, Massachusetts

Set, sound and lighting designers, Wilson Chin, Christian Frederickson, and Alan C. Edwards.

This will be the last of the entries on this page.

A new phase starts now, and we, the creatives, are all eagerly looking forward to where it goes…

Join us in New York City at Cherry Lane Theatre this Fall, September, 2019 for American Moor off-Broadway and beyond. We’re thrilled to have you with us.

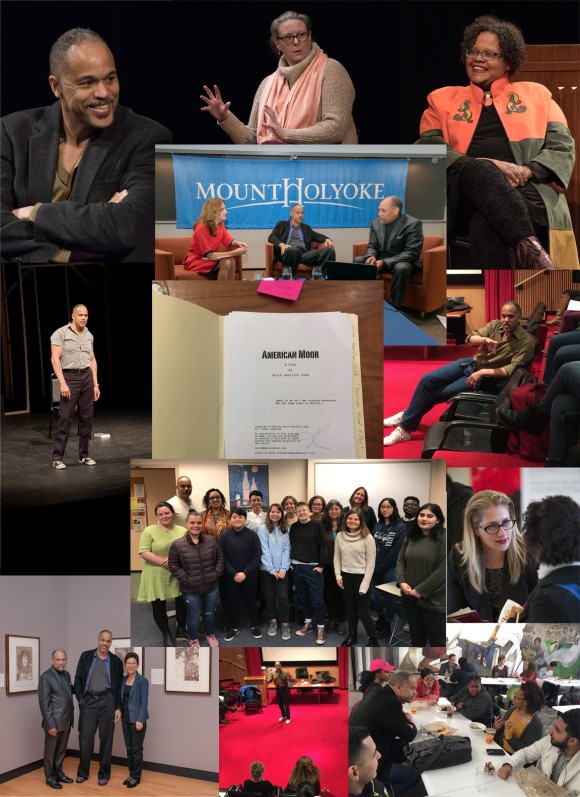

All This Activity Around One Little Play…

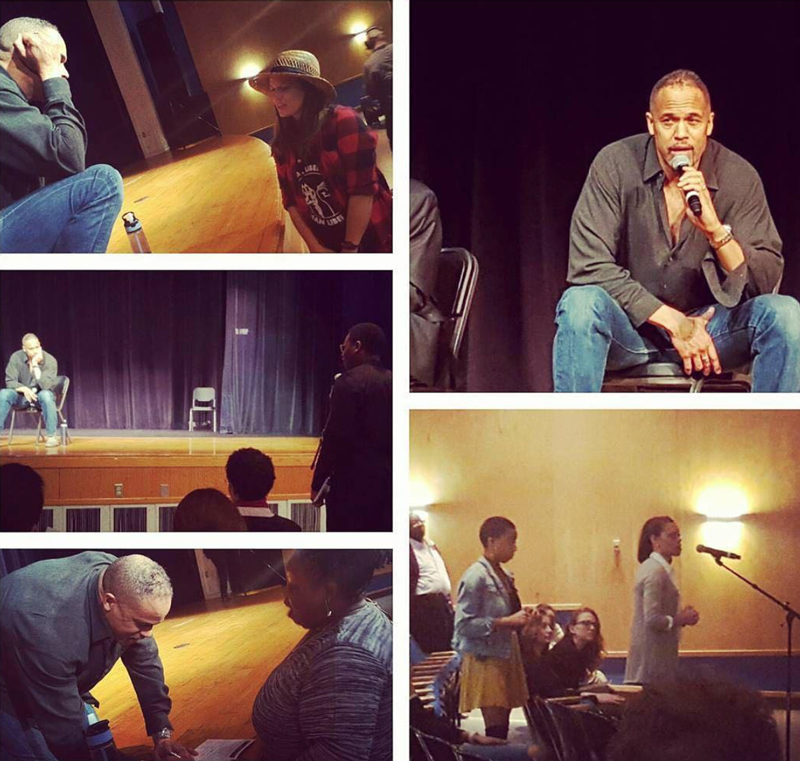

American Moor on the Campuses of

Mount Holyoke College, University of Massachusetts,

and Amherst, 11/2 – 11/15/18…

So this was new…

Fourteen days over three campuses, five performances of American Moor, and classroom interaction in classes ranging from “Intro to Literature” and “History of Performance” to “Diversity, Inclusion, and Everyday Democracy” and “Race, Racism and Power,” a round table discussion, a symposium or two… We sat and spoke with renowned scholars and visual artists. My play and I had never done anything like this before. The visitor to the web page here can scroll down and read about other college engagements. They all had purpose and value.

Top three photos credit: Jon Crispin

Clockwise from center: Director, Kim Weild; Scholar, Kim F. Hall; Umass Professor, Marjorie Rubright

Lower Left: Artist, Curlee Raven Holten, and Mt. Holyoke Art Museum Director, Tricia Y. Paik

Upper Center: Mt. Holyoke Professor, Amy Rodgers, and Curlee Raven Holten, visual artist and Director of the David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland

But this was another animal entirely. It was as if American Moor served as the nexus for any number of disciplines to converge and understand their place in this story. A Muslim student from Saudi Arabia stopping me on campus wept to discover upon seeing a performance that “his” story was her story, that she could not be the fully actualized individual in her new life as an American college student. Another small woman—a student as unlike me in age, gender, race, and life experience as any two people could be—steps up to speak with me after a symposium. She’s tracked the protagonist’s sore shoulder from the opening of the play through where, driving towards the last third, he speaks of how his injury now impedes upon his dreams because, aging, his body will no longer do the work to repair itself so well, and she tells me that she is a violinist and a good one, and that she doesn’t know, even as young as she is, if her shoulder will allow her to be a great violinist, and that she is afraid.

I don’t know what else to say…

Two Mount Holyoke students took me to breakfast. They wanted me to account for how Desdemona is addressed in my play, or, just as important, how she is NOT addressed, and only referred to, for the most part as they had perceived it, through images of violence against women. I’m still wondering if they were satisfied with my answers. Ultimately, it was, for me, just another instance of viewers finding themselves somewhere in the play, and wanting to defend, define, deny, or discuss their complicity.

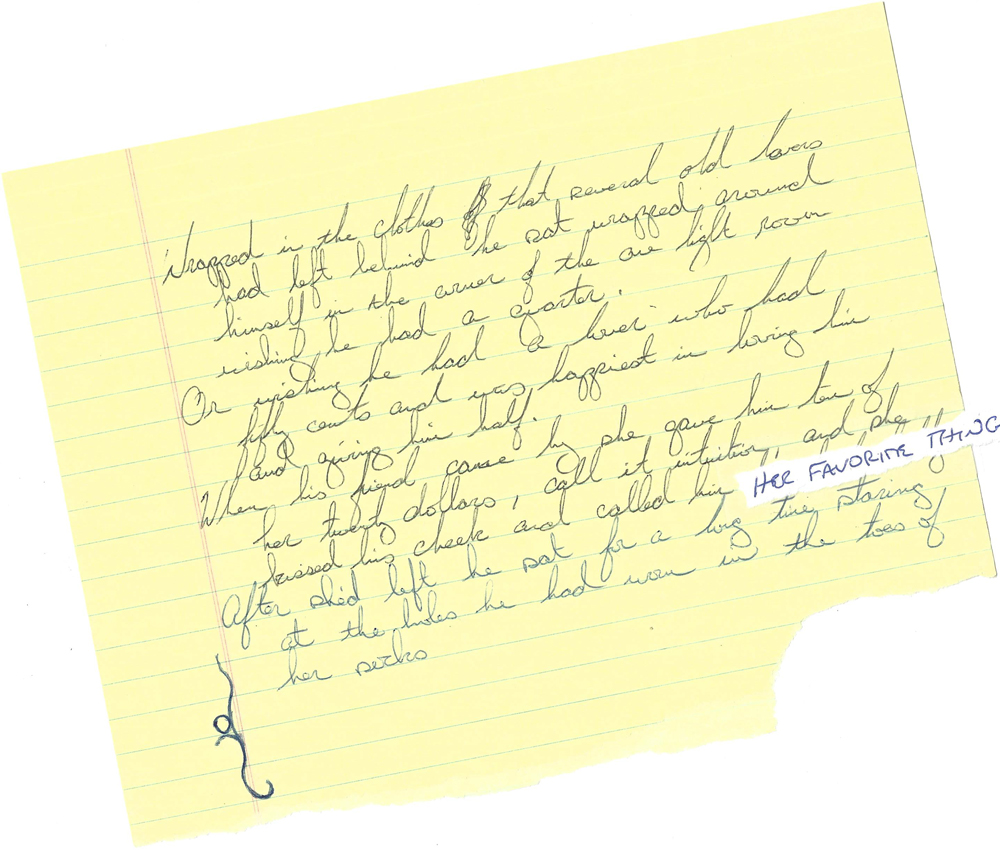

This is mostly a document in photos and short video clips. I’m hoping they can tell the story better than I can. It’s not my favorite thing to tell the story at all, but I hope rather that it begins to tell itself if we just keep showing up. I can’t pretend that everything that audiences are finding in this play I intentionally put there… but something did… Documenting these endeavors as they come and go by is my responsibility to whatever thing has done that.

Holyoke Post-Perf Comment (Complicity) from Keith Hamilton Cobb on Vimeo.

Holyoke Post-Perf Comment (Dir. Modality) from Keith Hamilton Cobb on Vimeo.

Amherst Professor Comment Post-Perf from Keith Hamilton Cobb on Vimeo.

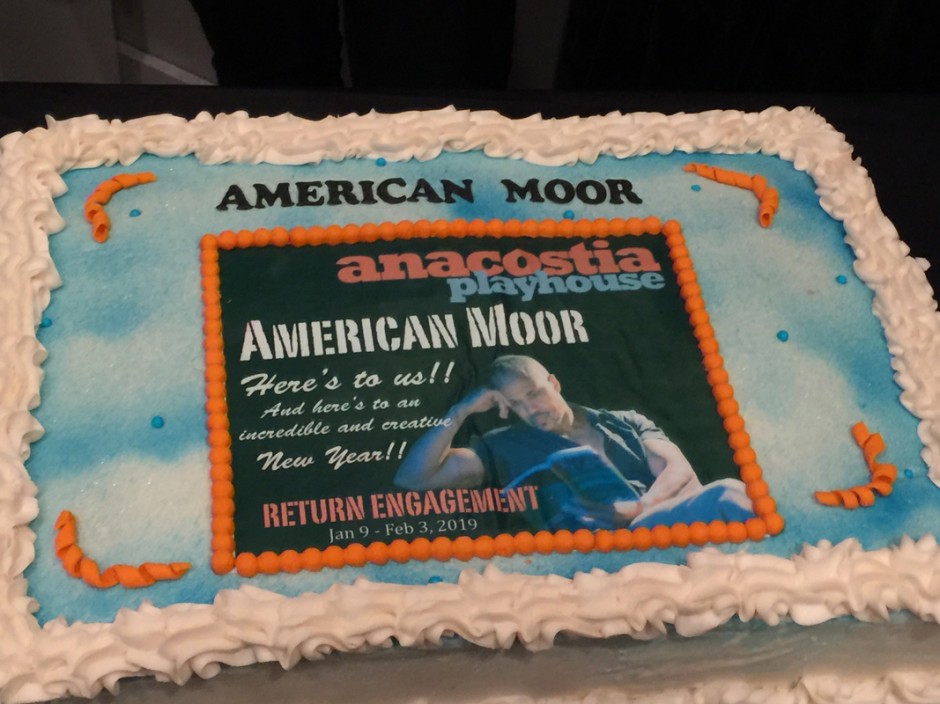

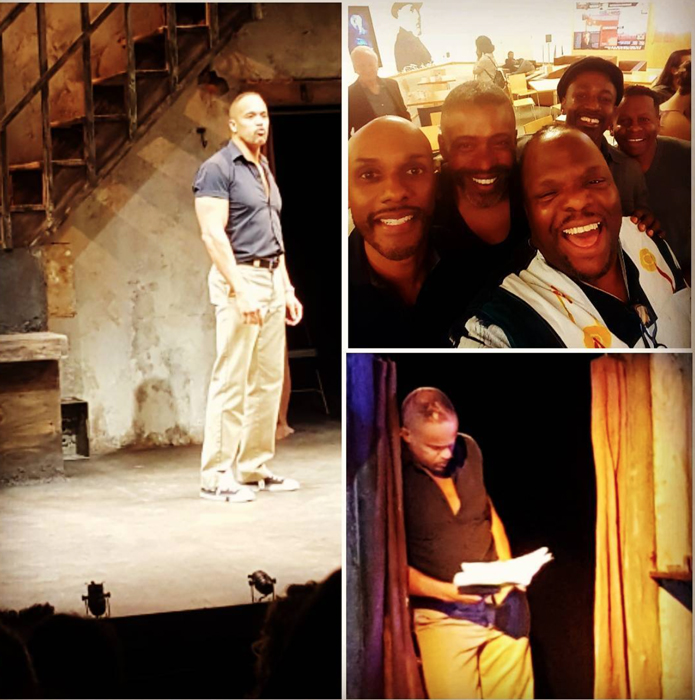

Washington, DC Return Engagement

Moor in Anacostia – Again…

The January production of American Moor at Anacostia Playhouse was another triumph if you listen to the local press. What I should have done was captured photos and video of audience and audience reactions the way they do to advertise a project heading to New York. As per usual, however, we were always short staffed. Theatre on a shoestring is like that, no matter how good it is, no matter how many people turn out and are moved by it. There are just too many tasks to undertake, and too few sufficiently remunerated people to get it all done efficiently. I should be used to it by now. American Moor has been evolving into the piece of art that it is for over six years in collaboration with little theatres, and underfunded theatre makers. And at the end of the day, what slips through the cracks is most often the documentation that suggests just what a wonderful project we’re pushing… So I don’t have a lot of imagery here of audience, but only a few that speak of our time there.

Like this…

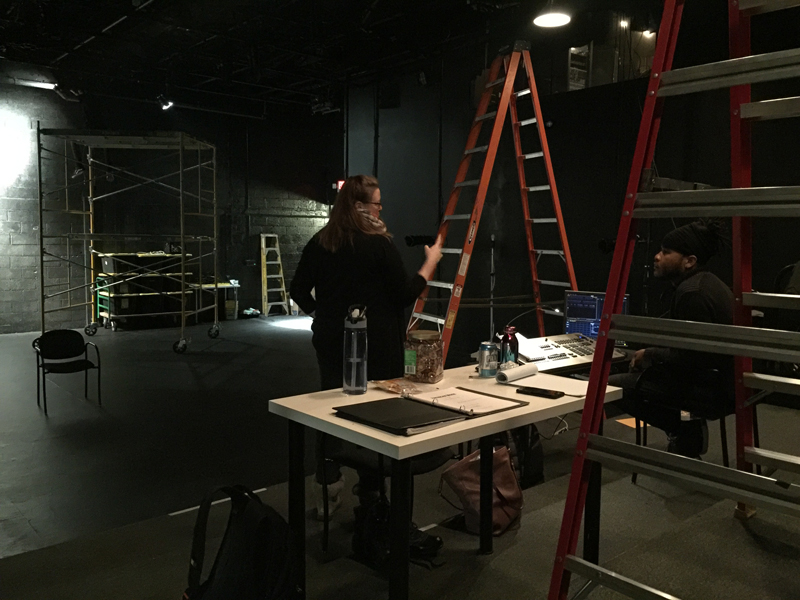

Rehearsal Day 1… A black box in disarray, and director, Kim Weild in conference with lighting designer, John “Juba” Alexander.

And these…

Set designer for upcoming 4/19 Arts Emerson production, Wilson Chin, director, Kim Weild, Actor, Josh Tyson

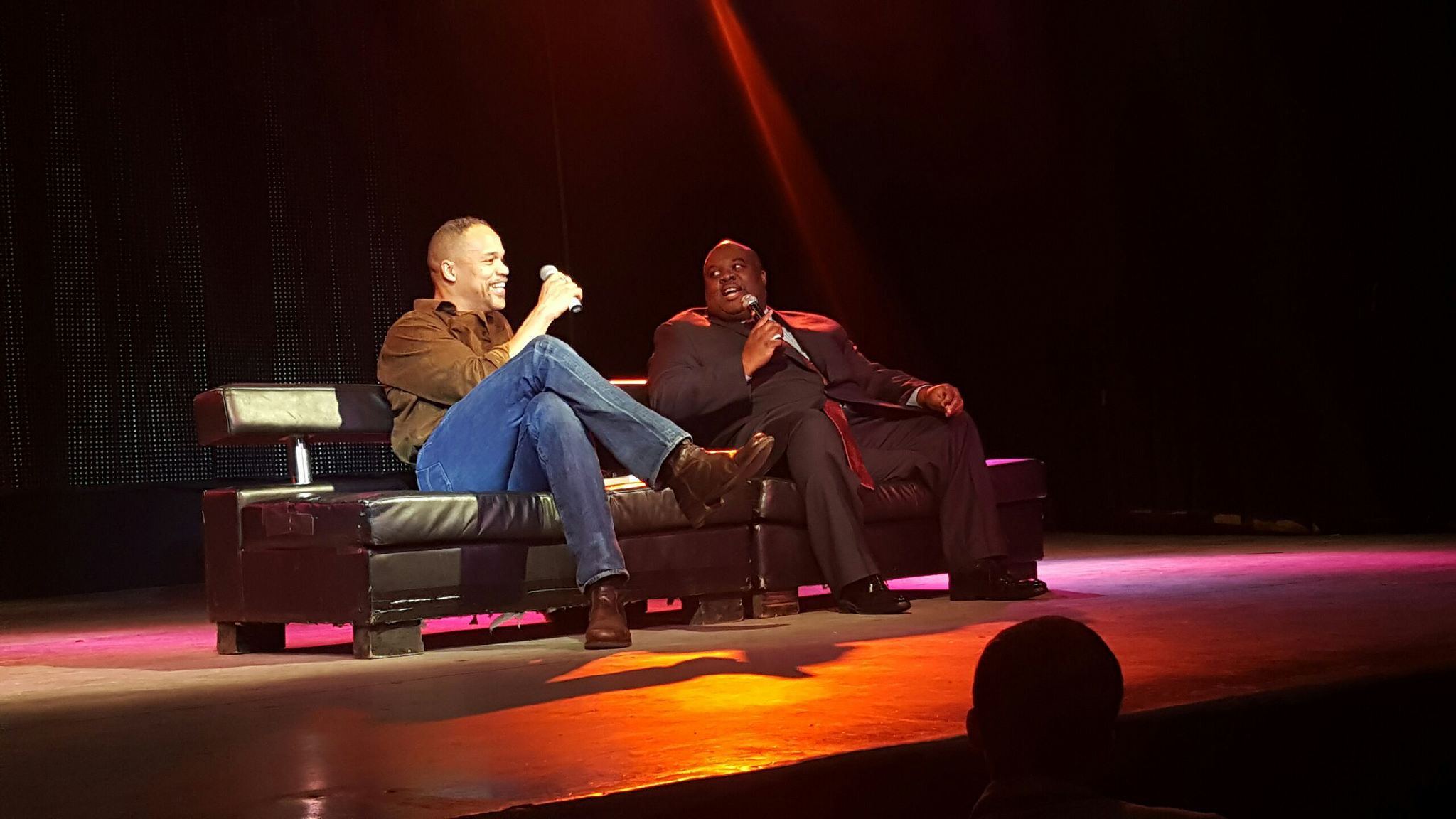

With Kojo Nnamdi, host of The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU Radio

Artistic director of Anacostia Playhouse, Adele Robey, director, KIm Weild, assistant to the director, Sisi Reid, lighting designer, John, “Juba” Alexander, actor Josh Tyson

This was an important stop in our 5 Destinations/5 Presentations that started back in New Jersey at Luna Stage Theatre last August, and will culminate at ArtsEmerson in Boston in April — not only because we had a good run, but because it was a return to a theatre that has believed in this playwright and this piece of theatre from the beginning. And belief is what it takes, not just belief in me and my creative team, but belief that theatre can save our lives, and teach our hemorrhaging culture to heal. It meant everything in the world to all of us to be able to collaborate once again, make new friends and colleagues, engage with new audiences, and grow together.

With gratitude, we are all looking forward to Fall of 2019. Seven years of work is coming to fruition. Stay tuned.

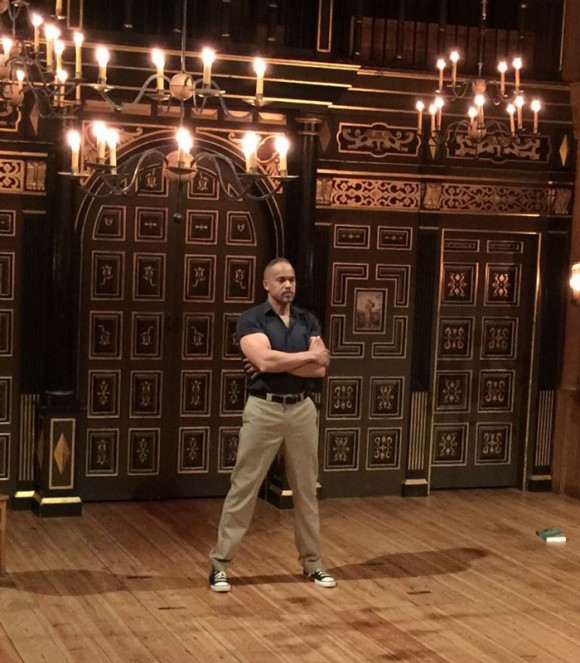

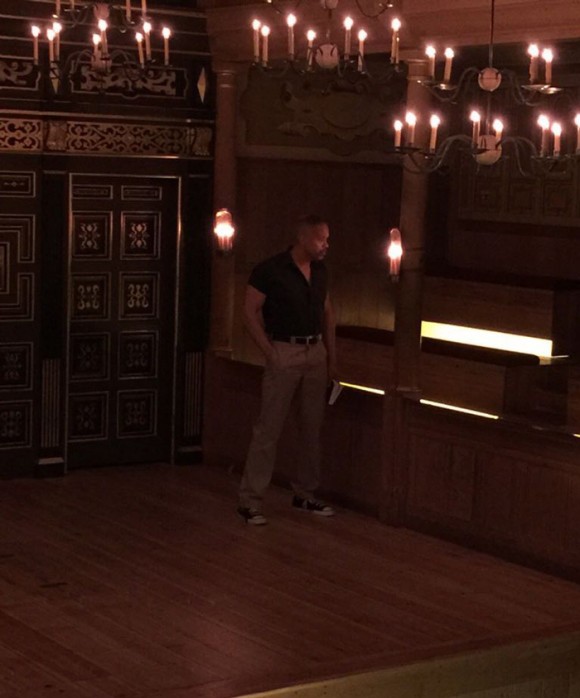

An Extraordinary Thing Happened at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London

London, 8/12/2018…

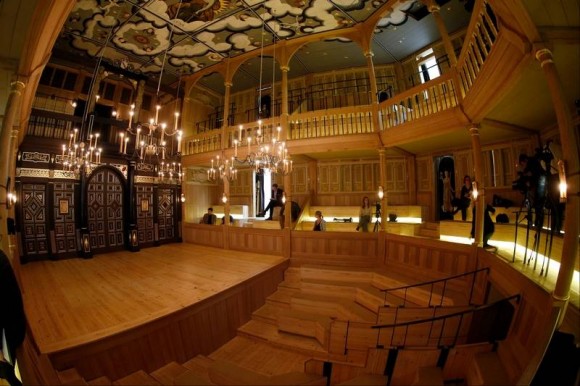

I had only been through once, years ago, doing a fan appearance for Gene Roddenberry’s Andromeda. And that had been for no more than a couple of days. I had never played on any of its stages, much less a stage built from a 17th century design and lit by candles in six chandeliers hung from the ceiling. It was certainly nowhere that I had ever envisioned performing American Moor. But there we were, with a rapt British audience of educators, scholars, actors, and laypeople. Odd… Wonderful, but odd… Because I suppose that this stop on the Five Destination/Five Presentation 2018/19 performance arc of American Moor never would have happened had it not been for the Shakespeare and Race Festival that The Globe Theatre was convening, and the urging of The Folger Shakespeare Library who partnered with The Globe on the event. Given the response to the performance — given the response to every single performance of American Moor that has ever been done anywhere — one would think it should be a whole lot easier to hand one’s good works to the world. But the fact remains, we would not have been on THAT stage with THIS show, ever… But we were…

It’s quite an arc, is it not, beginning in a lecture hall on the campus of Westchester Community College? There is for me a powerful symbolism in landing upon the Sam Wanamaker stage, and playing a play about American perspectives on Shakespeare through the instrument of a black American Shakespearean. Of course, the play is about much more than that with Shakespeare, Othello, and me as its vehicles. And of course, we know by now that no one persuasion of human being responds to this work; that it is in fact about a set of human conditions that are no less present in the UK than they are in the United States. Whether one suffers under those conditions, or benefits from them, all can recognize that the play is talking about them. All that really surprised me was this moment, in this theatre, in the arc of history, for Shakespeare and me.

It’s quite an arc, is it not, beginning in a lecture hall on the campus of Westchester Community College? There is for me a powerful symbolism in landing upon the Sam Wanamaker stage, and playing a play about American perspectives on Shakespeare through the instrument of a black American Shakespearean. Of course, the play is about much more than that with Shakespeare, Othello, and me as its vehicles. And of course, we know by now that no one persuasion of human being responds to this work; that it is in fact about a set of human conditions that are no less present in the UK than they are in the United States. Whether one suffers under those conditions, or benefits from them, all can recognize that the play is talking about them. All that really surprised me was this moment, in this theatre, in the arc of history, for Shakespeare and me.

The Jacobean stage, with its candlelight and its seating arrangement offered us some challenges that resulted in some changes to how the play was played. We could not hide the director. Unlike a contemporary spaces there was no control booth where the actor could stand and view the action on stage, speaking his lines from there so that they came across to the audience as an omnipresent, disembodied voice, as the role had been originally conceived and written. We were able to experiment with the director’s actual presence in the audience during two performance at Luna Stage Theatre Company immediately before flying for London, so we weren’t totally unprepared, and it worked well in both venues. What we lost, however, was the voice as coming from within us and also without, from somewhere and nowhere; the voice born of cultural norms and narratives that no one can pin point and tell to shut up because it is as deniable as it is present.

The Jacobean stage, with its candlelight and its seating arrangement offered us some challenges that resulted in some changes to how the play was played. We could not hide the director. Unlike a contemporary spaces there was no control booth where the actor could stand and view the action on stage, speaking his lines from there so that they came across to the audience as an omnipresent, disembodied voice, as the role had been originally conceived and written. We were able to experiment with the director’s actual presence in the audience during two performance at Luna Stage Theatre Company immediately before flying for London, so we weren’t totally unprepared, and it worked well in both venues. What we lost, however, was the voice as coming from within us and also without, from somewhere and nowhere; the voice born of cultural norms and narratives that no one can pin point and tell to shut up because it is as deniable as it is present.  What we gained was the audience being able to make a tangible distinction between the players. It took the argument out of the abstract. Some called that a positive dramatic shift. Others — and I think I — called it reductive. But I don’t know. That IS what this #MakingTheMoor hashtag is all about; what this Five Destination/Five Presentation adventure is supposed to find us. What works best? What creates the maximum impact? What tells the entirety of the tale most authentically?

What we gained was the audience being able to make a tangible distinction between the players. It took the argument out of the abstract. Some called that a positive dramatic shift. Others — and I think I — called it reductive. But I don’t know. That IS what this #MakingTheMoor hashtag is all about; what this Five Destination/Five Presentation adventure is supposed to find us. What works best? What creates the maximum impact? What tells the entirety of the tale most authentically?

Something else that I consider a net gain was the audience presence in seating galleries on either side of the stage itself and rising up a second story above the stage floor. It was a small stage, maybe 15 feet or so across. Given the intimate audience interaction that the play seeks, the Wanamaker configuration created a pressure cooker environment that upped the energy, allowing me true face to face communion with spectators. While the play ultimately wants lighting and scenic values, I would seek the intimacy of houses like this where audiences draw close to share in what is essentially a communal experience.

The Wanamaker and Luna Stage were both “stand on the stage and speak” performances. The Wanamaker had its atmosphere lent by candlelight, but there were no lighting effects or stage pieces to support the performance as was so in Boston, and at the Signature Theatre Center presentation in October 2018.. The script had to support itself. The great thing is that it can. It always does. Still, it has been evolving too, ever tighter, ever more succinct. These growing pains are difficult. There will need to be in the published academic version of the text a section for pages excised from the playing script that are not gone because they are not good, but because the matters upon which they treat are too big and impossibly complex to be made to fit. No part of this is easy, this play, the playing, the producing, the selling, or the issues around which the narrative revolves. But it is profoundly important, “if I do say so my damn self,” like conversations that continue about race and cultural responsibility in America and in the UK, and in the rest of the world.

The Wanamaker and Luna Stage were both “stand on the stage and speak” performances. The Wanamaker had its atmosphere lent by candlelight, but there were no lighting effects or stage pieces to support the performance as was so in Boston, and at the Signature Theatre Center presentation in October 2018.. The script had to support itself. The great thing is that it can. It always does. Still, it has been evolving too, ever tighter, ever more succinct. These growing pains are difficult. There will need to be in the published academic version of the text a section for pages excised from the playing script that are not gone because they are not good, but because the matters upon which they treat are too big and impossibly complex to be made to fit. No part of this is easy, this play, the playing, the producing, the selling, or the issues around which the narrative revolves. But it is profoundly important, “if I do say so my damn self,” like conversations that continue about race and cultural responsibility in America and in the UK, and in the rest of the world.

There is a part being played here that not enough people know about yet. We saw that when we played the Wanamaker playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe, London, and talk of the performance fueled the conference for the week to follow. The English audience heard and spoke back to the play with an intensity that rivaled any of our American audiences to date. What were they hearing? And what would they have not heard had we not had the opportunity to present this to them.

There is a part being played here that not enough people know about yet. We saw that when we played the Wanamaker playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe, London, and talk of the performance fueled the conference for the week to follow. The English audience heard and spoke back to the play with an intensity that rivaled any of our American audiences to date. What were they hearing? And what would they have not heard had we not had the opportunity to present this to them.

Now… onto the third destination, four performances on the campus of Mount Holyoke College and the two weeks of programming that surround them. We’ll see what changes. We’re showing up. “Mercenary actors, mercenary soldiers, that’s what we all do, and feel the holy pleasure of God in the act.”

FIVE DESTINATIONS / FIVE PRESENTATIONS

#MakingTheMoor Embarking on Nine Months

of American Moor in The NorthEast and London

I write this just a week or two away from returning to the stage with this theatre work of mine that has been silent for nearly a year. After garnering major honors for our 2017 Boston production, we are back at it, creatively insatiable and chronically dissatisfied. The play in Boston said everything that the play should say, if indeed it should “say” anything. It’s not about sending messages, but about presenting truths, I think, and sharing them with audiences who may not have ever considered those same facts in the way that you do. I think we did that to great success. It might not quite have looked exactly how we, the creative team would most have liked it to look. But we’re never quite sure. It is the audiences that have come out to experience the play in every city, their responses, their emotional engagement that continue to shape the look of this play, a piece of theatre so much about all of us, and what we are living right now.![]()

FIVE DESTINATIONS / FIVE PRESENTATION

AUGUST 7TH AND 8TH: Luna Stage Theatre, West Orange, NJ

Tickets Available Now!!

AUGUST 12TH: Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London, UK

Tickets Available Now!!

NOVEMBER 8TH – 10TH: Alice Withington Rooke Theatre, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA

JANUARY 3 – FEBRUARY 3: The Anacostia Playhouse, Washington, DC

APRIL 10 – 21: Arts Emerson, Robert J. Orchard Theatre, Paramount Center, Boston, MA

Tickets Available Now!!

Our presentation on the set of Susan-Lori Parks’ Fucking A at the Signature Theatre Center in Manhattan last October made us hungry for a set. We had been doing American Moor on bare stages everywhere we went. That’s more or less how the show was written to be played.  But in order to be granted the opportunity to present the work to a Manhattan audience at a central venue, we had to agree to put it up in a single afternoon, and to work on the set that existed in the space at the time we occupied it. We had to get in, light, stage, rehearse, and perform the show for audience twice in a single day. The process, as processes under pressure often do, lead to some remarkable discovery. The set, that was altogether foreign to the play we were presenting, focused the work in ways that we had not expected, for us, and we think for our audiences as well. We have been on the hunt for our definitive set and lighting design ever since, and hoping to discover it somewhere among these many dates ahead. But again, it was the audience response that indicated most strongly to us that something had shifted. They experienced the performance as if the set had been our intention all along. Those who had seen the show before expressed how it made a particular new sort of sense played there.

But in order to be granted the opportunity to present the work to a Manhattan audience at a central venue, we had to agree to put it up in a single afternoon, and to work on the set that existed in the space at the time we occupied it. We had to get in, light, stage, rehearse, and perform the show for audience twice in a single day. The process, as processes under pressure often do, lead to some remarkable discovery. The set, that was altogether foreign to the play we were presenting, focused the work in ways that we had not expected, for us, and we think for our audiences as well. We have been on the hunt for our definitive set and lighting design ever since, and hoping to discover it somewhere among these many dates ahead. But again, it was the audience response that indicated most strongly to us that something had shifted. They experienced the performance as if the set had been our intention all along. Those who had seen the show before expressed how it made a particular new sort of sense played there.

We start with nothing again. At Luna Stage in New Jersey, we put the play on its feet again and prepare it for the London engagement. We are on another bare stage, with our audience who will inform us with their reactions and interactions what’s still working… and what needs work… In London, at Shakespeare’s Globe as part of the Shakespeare and Race Festival, the unadorned stage of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse will again give rise to innovation. American Moor by candlelight in a Jacobean Indoor Theatre??!!  What an odyssey that promises to be!! And this, a totally new audience, with perhaps a different set of sensibilities altogether, experiencing the matters of the play through their British perspective of Shakespeare, race, and America. They are bound to have something to say, and we are eager to hear it.

What an odyssey that promises to be!! And this, a totally new audience, with perhaps a different set of sensibilities altogether, experiencing the matters of the play through their British perspective of Shakespeare, race, and America. They are bound to have something to say, and we are eager to hear it.

Back in The States all bets are off. We do a two-week residency and five performances on the campus of Mount Holyoke College, engaging with the students there and on the sister campuses of UMass and Amherst. The college engagement is a thing unto itself, unlike anywhere else we perform, or any other work we engage in. While we are moving more and more into the commercial arena, the communion and communication with students in and around this play has always been, and will continue to be vibrant, revelatory, and rewarding.

A return to Washington DC follows. The Anacostia Playhouse was the venue in the summer of 2015, where the play first came to the attention of the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the library has been a staunch supporter of the development and exposure of the work ever since. So this will be something of a homecoming in the new year. Much to celebrate, and all of the DC audience that missed the experience the first time around.

The spring of 2019 brings us back to Boston. We really need to call that a second homecoming, because it is returning to the city that embraced the work with passion in the summer of 2017, bestowing upon us two IRNE Awards and an Elliot Norton Award. In the hands of our hosts Arts Emerson in the beautiful Robert Orchard Theatre of the Paramount Center, we will most certainly have arrived somewhere, perhaps with all the pieces in place that we have been searching for, perhaps not, but again, letting the wider Boston audience come and take part in the conversation that so many are having with us. What is the role of a lifetime? What is the role of a life?

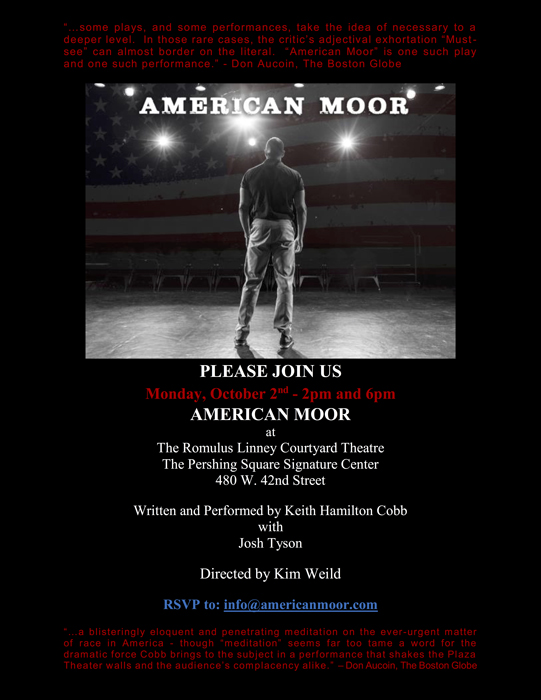

One Night in Manhattan for any Interested Parties

We did two shows on Monday, October 2nd, 2017

at the Signature Theatre Center

on the set of Susan-Lori Parks’ play, Fucking A.

I haven’t got a lot to say about it except perhaps that the shows were astounding, for me if not for anyone else. We were in at 10am, were performing by 2, and played two houses before 8 that night. That seat-of-the-pants thing can be magical sometimes. Not knowing what’s going to happen usually means anything is about to happen. Maybe it’s a little like that adrenaline thing that type-T people talk about experiencing when they jump off of cliffs and crazy shit like that…

This was a by-invitation-only event. It looked something like this:

Performing on the set for another show was new. A bare stage is what we were used to. And yet, the premise of the play is that an actor walks into an audition… The audition could be anywhere.

Performing on the set for another show was new. A bare stage is what we were used to. And yet, the premise of the play is that an actor walks into an audition… The audition could be anywhere. He will have to adapt, use what’s there. So the performance that day in the Linney Courtyard Theatre was like the play. Actually, everything in life is like the play… At least that’s my experience.

He will have to adapt, use what’s there. So the performance that day in the Linney Courtyard Theatre was like the play. Actually, everything in life is like the play… At least that’s my experience.

Upper right from left to right: Keith Boykin, CNN, Musa Jackson, model and Harlem ambassador, Kevin E. Taylor, Author Minister Activist, Gordon Chambers, Grammy award winning songwriter/singer, Mark Forrest, entertainment agent

American Moor in Boston

A Turning Point

The Boston Production,

Summer 2017

The production of American Moor that ran at The Boston Center for the Arts Plaza Theatre from July 20th through August 12, 2017 was the longest run of the play in performance since its inception nearly five years ago. It was a joint production by a small company in residence at the Boston Center for the Arts, OWI (Bureau of Theatre), and New York based Phoenix Theatre Ensemble. The house was a 150 seat black box, and Boston… was Boston…

The last time I’d played this city was 1992. It was with The Huntington Theatre Company playing Arviragus in the Larry Carpenter production of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline.

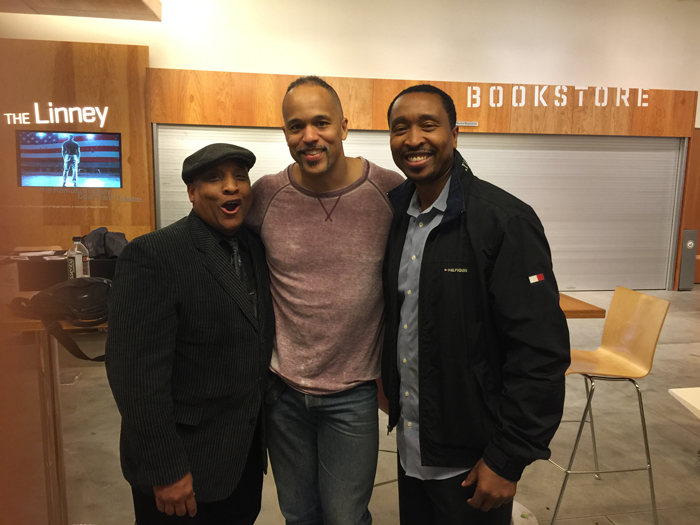

In the 1992 production of Cymbeline at The Huntington Theatre Company, Boston, w/ Jack Aronson (center) and Matthew Loney (right)

It was a different city then… That that I was able to see of it this time around – so much of my time was spent cranking out the one-man performance every night – had changed drastically. I’m sure that is the dynamic with all major American cities. There always seems to be more high end housing, which would lead one to believe that there are more and more people with a ton of money. And yet, somehow, theatre continues to struggle. At least my theatre did. Not that we were not a success in Boston, the responses were glowing. But no one made any money, and this is the glaring irony of the American Theatre. It can’t be about money. Well… I mean, it can be, but when it is, it most often isn’t very good, or very important. Money, the larger sums of it, generally gets spent on things that are somewhat assured to make even greater sums of it. Taking care of one another is not a for-profit venture. Subsidizing things that are for the general health of the populace at large is considered a bad bet. But more on that later.

Regardless, this was a huge step in the development of this work. We were, for the first time, able to more fully (though not fully enough) explore aspects of set, and lighting, and within that exploration discover moments of on-stage life and text that we had not known were there. When I say “we” I mean my director, Kim Weild and I. She has been guiding the development of this piece of theatre for the past two years.

And American Moor is a play about so many things. I don’t doubt we will still be discovering new things a year from now. In the post-performance discussions that we held twice a week, there were always new insights to be mined. No two people respond to this play in the same way. It is always a deeply personal journey for every individual, which speaks, I think, to a universality of theme.

Through the interactions with audience we have found that this play about race is not a play about race at all if one is inclined to see beyond the obvious. I find myself saying more and more often to anyone who will listen that the internal problems America is faced with are not a lot of different things. It’s one big thing with all the little things being manifestations of it. The unchanging fundamental nature of the human animal is at the root of all our cultural dysfunction. All of it, no matter what form it takes. The behaviors to which we all, to one extent or another, succumb are inherent to the species. Someone called the play “self-indulgent…” But how does one express the self without indulging the self? And further, in making such a comment, isn’t one, in essence, saying, I want to indulge myself by telling you that you are indulging yourself…”??? That which perpetually percolates in the minds of men/women, the primitive animals, above all is ego and fear, the one is the definer, the other is the arbiter of ALL that is defined. I challenge anyone to show me that this is not so. And all of our cultural dysfunction arises from this simple truth. Those who are aware of this within themselves tend to find empathy with the characters in the play, and with others outside of their own societal situation. Those who are not tend to identify, as ego does, with one side or the other of the surface argument, and with any that see it as they do, while ignoring, or missing altogether, the myriad manifestations of their fear-based culture that lie beneath it. They, ironically, literally become the embodiment of the issue being portrayed on stage; the inability to interact beyond personal perspective… To understand this, however, you’ll have to see it.

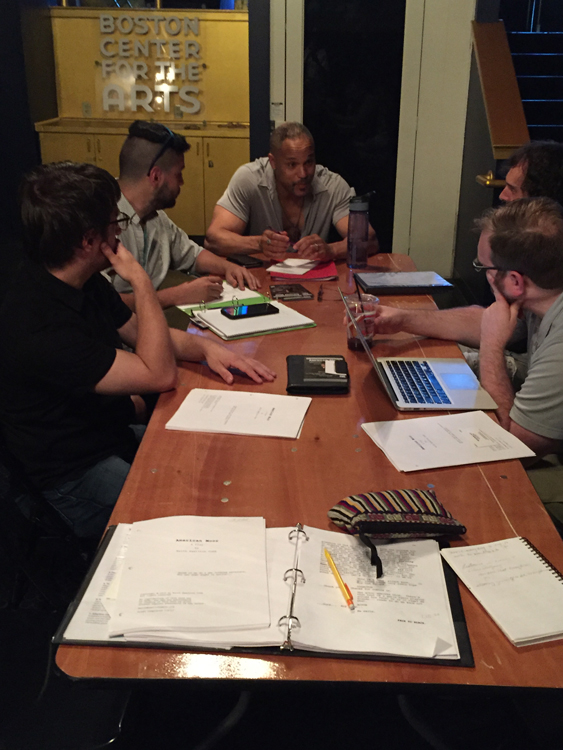

Here we are again. From left: Andrew Duncan Will, Sound Designer, Kim Weild, Director, Matt Arnold, Actor, Shaoul Rick Chason, Dramaturg, Me, and Caleb Spivey, Stage Manager

If you had seen the Boston production from where I stood, you would have experienced not only the struggle of the actor as portrayed on-stage, but as the actor himself, in calorie deficit, lacking sleep, body-misalignment, and big fat rats in my dressing room. I don’t suppose I’m looking for sympathy. I am however hoping for empathy, just like the character in the play… I would like people to understand the sheer magnitude of the gap between a stack of stellar reviews and all that needs to be done, dealt with, and endured to get them because of the culture’s general fear-driven inability to care for the arts. I’d like people to know that making theatre is very hard, and that there is no reason for anyone who does it to submit to that level of self-abuse except for an unflagging belief in humanity and the desire to nourish and nurture it, even while having to perpetually experience and acknowledge that humanity generally sucks…

We Are All Shit…

The Myth of Moral Superiority

Searching for nuance where it has never served our most immediate, individual ends… and why it is most necessary…

“…the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.” So said the now removed Battle of Liberty Place Monument that stood until April 24, 2017 in the city of New Orleans. So, let’s start at the beginning. Are we talking about “white supremacy” in the sense that white people are better than everyone who is not white, or are we talking about “white supremacy” in the sense that white people had control over everything? Regarding American governments, or I should perhaps say regarding that which governs America, the latter has always been true, to a large extent, from the moment of the country’s founding right on until now. The former, as a pesky point of scientific fact, has never been true in any form ever. A monument attesting to the facts of white control may be distasteful but, given the context wherein it was erected, it is difficult to call it inaccurate, or incorrect. From the time the white man arrived on the continent with a propensity for either exploiting or exterminating anybody who wasn’t he himself, he has been as in control as anyone ever was anywhere, and arguably, more or less, still is… To call it “wrong,” or “right” is a moral judgment that has to do with the pollution of facts by opinion, and the pollution of opinion by need; our problem in a nutshell. On the other hand, however, a monument that stands as a means of assuring the citizenry of a city in an American democracy, the majority of that citizenry being black, that white people were at some point somehow factually established as superior beings, or that they remain so, is not only specious in the extreme, but there isn’t a tenable argument that can be raised against such a monument’s removal. Read More →

Talking Shakespeare, Race, and the Practical Humanities

The Thing is The Thing: Acting – and not acting – Shakespeare while black.

This is a recording of a talk I was asked to deliver to open a two-day symposium entitled “Shakespeare, Race, and the Practical Humanities” on the campus of Lafayette College in Easton, PA on April 19th and 20th, 2017.

It will speak for itself…

American Moor at University of Pittsburgh-Bradford 1/30-2/3/2017

The week in Northern Pennsylvania was short; five working days really. The University of Pittsburg-Bradford is a small, beautiful campus, and the week saw it covered in snow. My host, Professor Kevin Ewert, who teaches theatre at the college, packed a great deal of interaction into that five days. I met with theatre students, students from the African American Student Union,

and a highlight of the trip, I met with Professor Ewert’s Modern Black theatre class at FCI McKean Federal Correctional Facility, where his students share a session once a week with a class of incarcerated men, all of whom had read American Moor. The feedback from this group was profound for me. This was the first time that the play had been presented to any group, not as performance, but as literature. The responses of the inmates were unique and immediate. Of course they would see in the play what has always been there, but see it in the starkest of terms, particularly the elements focusing on social justice.

The theatre students were most interested in inquiring about what possibilities there were for an actual life in the theatre. How does one pursue such a life and be reasonably comfortable in the belief that life will be livable. Of course I’ve no answers for such concerns. What young aspiring theatre people need to hear most, it seems to me, is that there isn’t much choice in the matter if you are innately driven to manifest your being through the arts. You may be miserable attempting to eek out a living, but you’ll be equally miserable, if not more so, attempting to live a life in an albeit “safer” way, yet one that does not honor your soul-labeling. In our interaction I did not get the sense that these students get to express much regarding their needs in art, or their fears born of those needs. I was happy to have the time just to engage the discussion. Communication is everything…

The students of the African American Student Union and I got to sit down to dinner, where I listened to them speak on the issues of Blackness and campus life that most concerned them. They were also helpful in generating an audience for the Thursday night performance of American Moor.

One last group that I was given the opportunity to speak with was an Art Appreciation class. This was a discussion that fed directly into many of the themes present in American Moor, most particularly ideas about who gets to make art, and who is to say what art is good, relevant, and/or worthy of attention.

Except for the inmates from McKean, of course, many from all of these groups were present for the performance. I played to a house of about 75 people in a playing space uniquely configured for our production. It was extremely intimate, with very little distance between me and the audience. This always allows me the ability to truly include them in the journey happening on-stage. Most often they seem happy to come along. The post-performance discussion was, as always, alive with audience expressions of the experience.

UPitt-Bradford, unlike FAMU and Southern Shakespeare Company, did not have the wherewithal to bring in the community beyond the college in the same way. The performance there was largely for students and faculty. I always feel as though one week, though better than the one-off nature of a couple of days, is still sort of a one-off in itself. I’m left wanting to do more, to explore more deeply, to ask and answer further questions, which are endless. The first performance is always rough. There needs to be at least two… When the production finds a home of its own for an extended run, that problem will ostensibly be alleviated. But there is stuff in the academic setting that I won’t find out in the world of the professional theatre. I suppose it’s nothing for me to dwell on, but just to take each new endeavor as it comes and for what it presents. I think lives were affected by the work of the week in Bradford, none the least of which was mine.

Post-Performance Video of American Moor in Tallahassee

Just a few brief clips of the work in Tallahassee.

This post performance discussion was particularly informative for me, as I saw that the work is beginning to expose levels of itself that only audience experience can reveal. Post-performance participants express connections to the play that are unique to them and to their experiences in life. I respond to their questions, but mostly I want to just sit back and listen to their immediate responses to the play. I learn so much just by hearing them talk.

A Southland Premiere

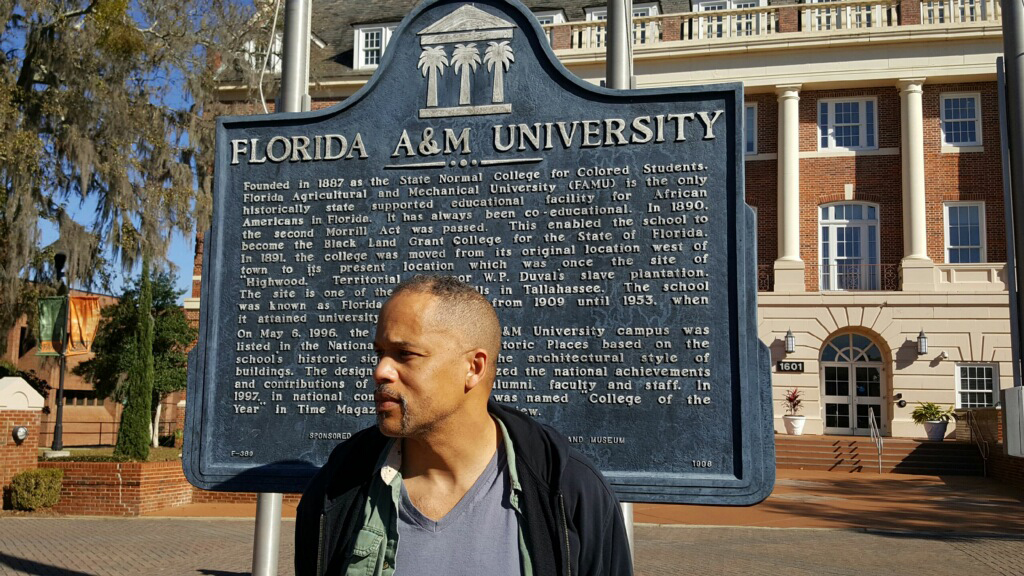

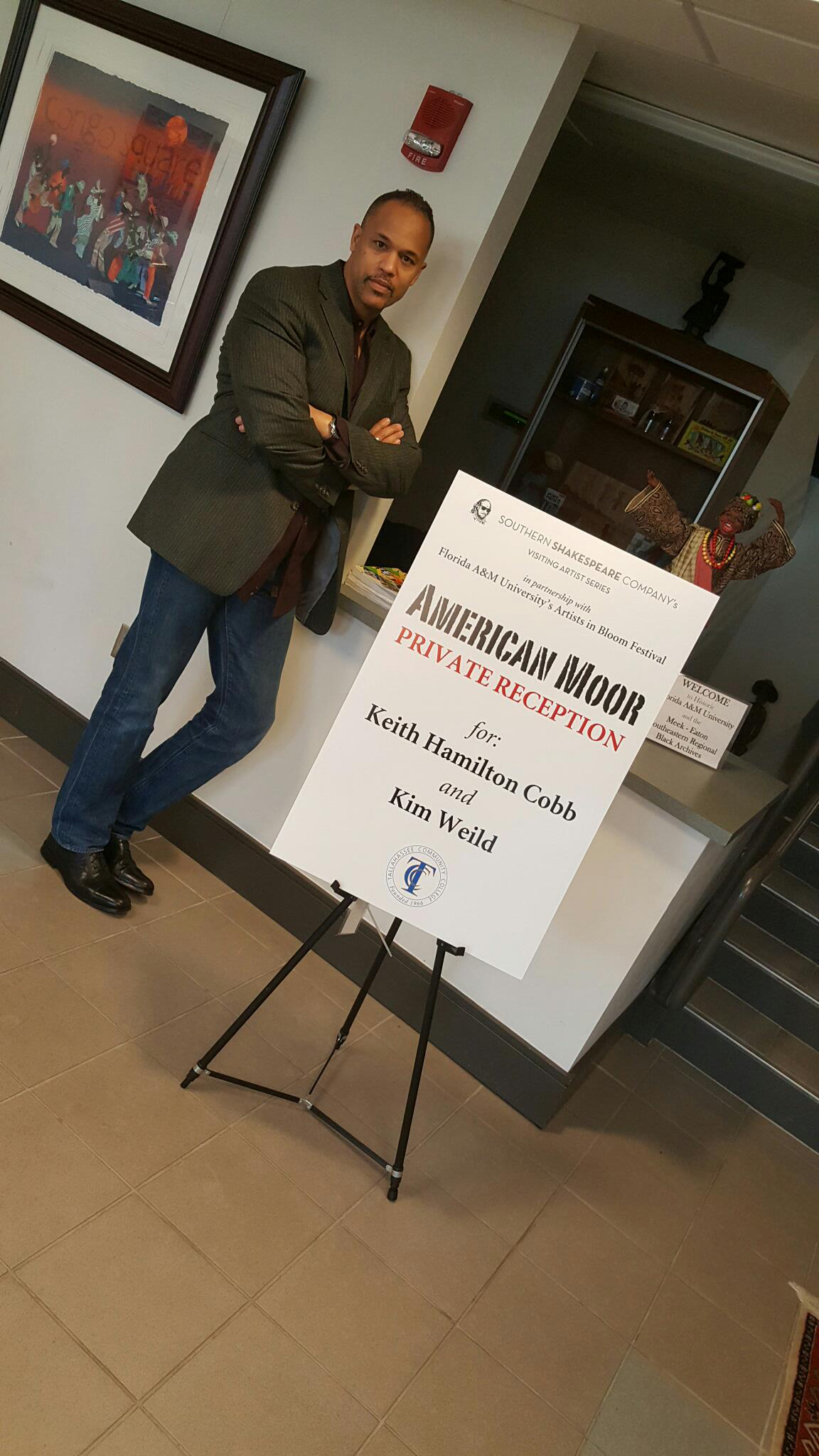

Southern Shakespeare Company and Florida A&M University Collaborate to Host Actor and Director and American Moor for a Week: 1/9-1/13/17

This experiment in community engagement was a first for American Moor AND for my director, Kim Weild and me. Southern Shakespeare Company is a small Shakespeare Company in Tallahassee, Florida with a focus on education. Not so small it seems, however, to stop them from taking an interest in American Moor, and rallying the resources to bring us to Florida for a week of work.

Their partners in this endeavor were several. Most prominently Florida A&M University played host to our rehearsals and performances in their Lee Hall Auditorium. While there we met and worked with college students from FAMU’s Essential Theatre Program, as well as with eleven-, twelve-, and thirteen-year-olds from Southern Shakespeare’s youth company called The Bardlings. We also met some wonderful people in the greater Tallahassee community when we attended an event hosted by Village Square, a non-partisan public educational forum. Their event was called “Created Equal,” and sought to stimulate constructive dialogue around matters of race and race relations. We were busy…

The production team: (from left) director Kim Weild; stage tech – Felix Anitra, and Nile; (front) publicist Pamela Daniels.

We had not had a concerted period of rehearsal for quite some time. Most of the recent outings for American Moor have been of the one-off model, where we quickly mount the show in a venue, do it, and go home. This was an experiment in residence, where we had several days to work, eat, drink, acquaint ourselves, and communicate with smart, engaging, theatre-loving people who believed in the work of this play as much as we did and do.

We played two performances to houses of about 500 people each night. Even this many years in, the post-performance responses from always diverse audience members astound me.

There is always some perspective or thought that someone will share that I’ve never heard before. Each new endeavor brings discovery.

Here are as many pictures from the week as it makes any kind of sense to stuff into a single blog post. There really isn’t a whole lot else to say but “Thank you.”

At Village Square’s “Created Equal” event: (from left) Southern Shakespeare Company Executive Director Laura Johnson, me, and director Kim Weild.

With noted writer and attorney, Chuck Hobbs, on stage at “Created Equal,” the Village Square event in Tallahassee.

Integrity in the Time of Post-Truth

An Actor Wonders How to Be in a Culture Devoid of Honest Self-Assessment

It’s Tuesday, November 15th, so how long is that after the presidential election? And that’s how long it’s taken for me to realize this most absurd of things has actually occurred. In fact, the level of absurdity is such that it cannot bear rational commentary. The only truth to be gleaned from the morass of sound that generated it, and that it is generating, is that it HAS occurred. We can try to put our brains around that fact if we like—it’s taken me a week—and take action from there. But I can leave the talking to the pundits of the entertainment news networks, who are wholly culpable in helping to bring this absurdity about. While I haven’t watched any television news since election night, I’m quite sure they are readily embarked upon the lucrative endeavors of talking about the absurdity that their talking about promulgated in the first place. They got you comin’ and goin’… It’s a helluva business… But I don’t have to invest. I don’t think any of it was my fault, and know that I wouldn’t be able to fix it if I tried. That doesn’t mean I won’t try. There’s much to do, but I don’t think there’s much to say at this point unless you’re selling something. It’s fucked in numberless ways, but there it is. And here we are…

If I’m going to talk, I want to talk about theatre. This is something I know. I’m an actor. I can impact this, a little bit with my talent, but that’s the cheapest of commodities. I can impact it more, much more, with something far more scarce, integrity, and the simple, but not easy act of showing up with all 110% of the artist in me ready to play, or fight, however you wanna bring it. Discussions of American theatre are important to me. We must have them because Read More →

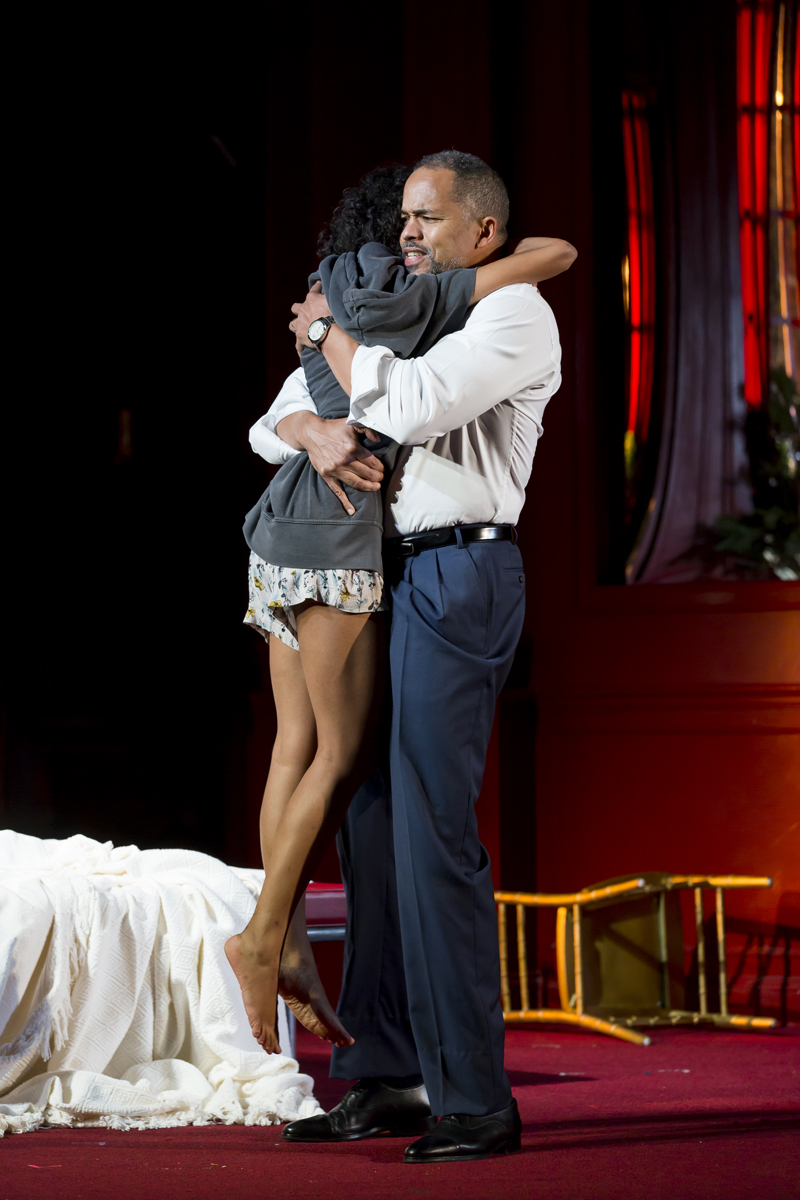

Romeo and Juliet at The Shakespeare Theatre Company

Romeo and Juliet at The Shakespeare Theatre Company, Washington, D.C., August – November, 2016

This was a long summer into autumn with many talented people and a company that has been in the Shakespeare business for a long time. An extended run, I mean it is Romeo and Juliet after all. I think you might draw a few more if you did West Side Story, but not many…

Lord Capulet is another one of those supporting roles that needs to be fleshed out. Because you can’t add text, and, in many cases, as in this one, text is removed to shorten the play, there is some work to be done to make him anything like a human being. The things that motivate his behavior have to be firmly rooted internally for them to appear to an audience without the text that might otherwise accompany them. There is also a process of nurturing each of the characters on stage to the point where they are able to assist in the telling of one another’s stories.

This Capulet was interesting, struggling clearly with his urges towards love and hate, and navigating the space between, if not wholly there.

Julius Caesar at Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival

Julius Caesar at Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival June/July 2016

This was a talented ensemble of seasoned professionals, with a young company of eager, intelligent and highly focused students at Desales University. The director, who was also the producing artistic director of the theatre, Patrick Mulcahy, was/is a seasoned professional and former actor who knew his Shakespeare. Ya gotta know your Shakespeare, y’all! He told a tight, intense, moving story with simple staging, costumes, and sets.

It helps, I think, when directing good actors, to have been one yourself. Too many directors, I find, have studied telling actors what to do without any real understanding of why and how actors do.

As the artistic director of a mid-tier Shakespeare festival with limited funds, it also pays to be deft at the husbandry of resources. I’ve always maintained that good Shakespeare can be done on a bare stage in jeans and t-shirts. But that probably doesn’t work quite so well if you are trying to sell it to the American masses, who are much better at seeing than they are at listening… Mr. Mulcahy was able to rally the requisite team of creatives to paint a compelling picture and tell a believable story without the benefit of uncountable riches, and I imagine he was able to do that as a manifestation of his extensive experience. Of course, experience doesn’t always guarantee any such result. Not all regional theatre experiences can I call successes, and some that are would be better termed “happy accidents.” But I think, in this case, that clear intention and an ability to work with and integrate all creative elements bolstered by a life already lived in the theatre were to be given the credit.

As for the play… I haven’t seen many Caesars who didn’t stalk about the first half of this play declaiming self-aggrandizing platitudes, and making themselves so damned annoying that nobody ever really gave a shit when they got knifed to death in the assassination scene. That’s sort of how Shakespeare wrote him, and he can be forgiven for the parameters of his form that sometimes left characters to stand as representations of a thing more than the authentic human incarnation of that thing with all its nuance and complexity. People aren’t simple. The way I see it, if we are telling stories about people, then no one in the story can be left as an unexplained idea, least of all the title character, or else the story isn’t ever really told… I didn’t want to be that guy. Patrick Mulcahy and I both thought it much more important to the play to make it rather ambiguous whether the issue was ever really Caesar’s conceit and ambition, or the egos and jealousies of his assassins. He had to behave in such ways as made people think about who he might actually be as a human being, not just what he represented. When you begin to recognize the levels in a man, you can begin, perhaps, to empathize. I wanted the audience to like him enough to mourn him when he died. I think we did that.

I think my director and I found old Julius a little justice.